Wildfires threaten Peruvian Indigenous communities and national park

This story was investigated by Mongabay’s Latin America (Latam) team and was first published in Spanish on our Latam site on September 15, 2016.

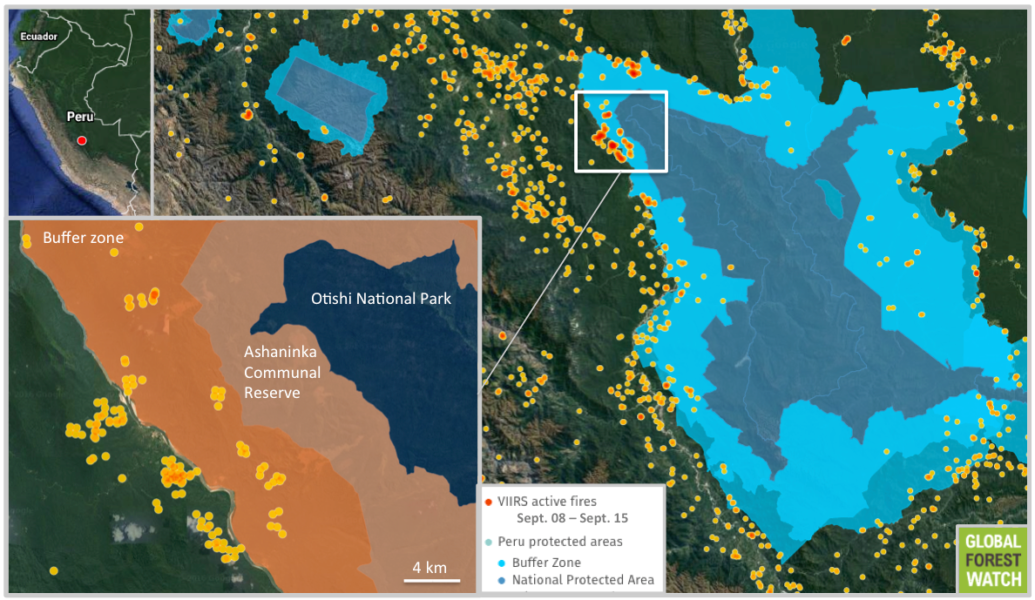

A major fire event has affected around 20,000 hectares of rainforest in the central Amazon region of Peru. Satellite data from NASA show several fires burning in the protected buffer zone around a national park and Indigenous reserve, and reports on the ground reveal the uncontrolled fires are having damaging impacts on local communities.

“The fire originated on the right bank of the Ene River, which is a valley that is part of Río Tambo District in the province of Satipo, Junin Department,”Iván Cisneros, mayor of Río Tambo, told Mongabay Latam. “In this section of the country, the Otishi National Park is located west of the Ashaninka Communal Reserve. A ring of communities borders the reserve. The fire is currently affecting this ring, and it has even reached part of the national park.”

Conservationists had previously warned authorities of the fires. In early August, 24 experts signed an open letter advising government officials in Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru about the issue. In Peru, a document was sent to the office of the Presidency of the Republic, the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Agriculture. Pronaturaleza – a Peruvian foundation for nature conservation – was responsible for sending the document. At press time, no response from the authorities had been forthcoming.

“We have sent an alert about a month ago. And the fire hotspots that our Brazilian friends were monitoring already showed fire two months back. Now, local authorities have to deal face to face with these fires, but they do not have the tools to do it,” said Ernesto Ráez, tropical ecologist and member of the Pronaturaleza Foundation to Mongabay Latam.

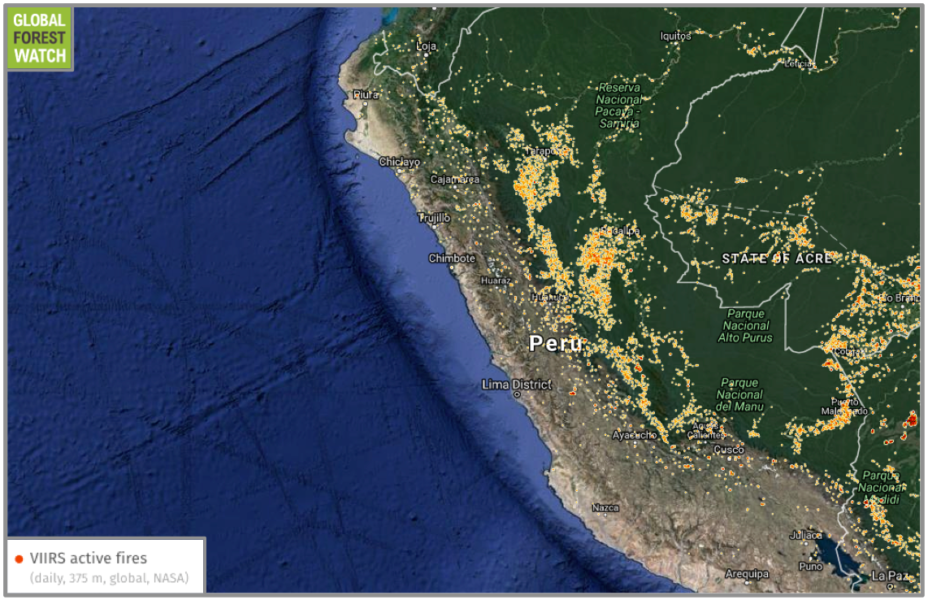

Wildfires aren’t just a problem in Junin Department, but are occurring all over the Peruvian Amazon. In all, NASA recorded almost 10,000 fires in Peru during the past week (September 12 to September 19).

Ráez further explains that there is no plan to deal with such emergencies: “even though the Forestry law mentions forest fires, plans have not yet been developed nor have the capabilities to address them. Now, the issue is not to attack the fires, it is to learn to avoid them.”

The alert

On September 13, villagers and authorities called to warn about a major fire that was affecting the right bank of the Ene River, according to Cisneros. Cisneros admits he is concerned about the situation, and more so after flying over the area where the fire happened.

“First there is no visibility [because of the] smoke clouds the area,” Cisneros told Mongabay Latam. “There is no wind from north to south in that area; the extension is 40 to 50 kilometers along the Ene River. The fire has crossed the river, which is unusual. There is fire on both sides (banks), which threatens communities, including those of Potsoteni and Caparucia. (The fire) has devastated staple crops and cocoa, I think it will damage about 50 hectares of cocoa.”

Two communities seriously threatened by the advance of the fire are Caparocia Potsoteni and Ashaninka. The situation had become so dire that on the morning of Thursday, September 15, a commission was sent by river to coordinate the evacuation and relocation of the residents of these communities, Cisneros confirmed.

As of September 15, there were 15 fire hotspots, according to the Peruvian National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP). Marco Pastor, a SERNANP official, mentioned that a SERNANP brigade entered the affected area a few days ago to assess the magnitude of the fire. He told Mongabay Latam that drier than normal conditions in the region may have contributed to the fires.

“We need an aerial survey. We are coordinating with the Peruvian Air Force to conduct one,” Pastor said. “Now we could say that there are 15 fire hotspots, maybe a little more, but these are spread across several sites. Why? Because they are triggered in places where vegetation is drier and areas of grassland vegetation.”

However, so far there is no official report confirming what started the wildfires, according to Cisneros, who said it is the largest fire event that has occurred in the region in the last ten years.

Ashaninka communities the most affected

Steffy Rojas is a member of the technical team of the Ashaninka central station of the Ene River (CARE), an organization that represents and defends the rights of 17 Indigenous communities. CARE has been working in the area for more than ten years. Mongabay Latam spoke with Rojas to find out what are the most affected communities and obtain information on the development of the fire.

According to Rojas, “there have been 11 locations directly affected: eight native communities and three rural communities. The situation has become more difficult due to the drought caused by climate change. There are 28 points of fire outbreaks, three around the Ashaninka Communal Reserve and four points just 950 meters away from the reserve. Since August, when the first reports of the fire started, there has been 36 kilometers of continuous fire spreading over 105 kilometers.”

This information coincides with the fire assessment made by a team composed of specialists from SERNANP, the National Forest and Wildlife Service (SERFOR), the Satipo Fire Company, the Peruvian Army and the Río Tambo District Municipality. In a preliminary report, provided by Rojas, they write that 11 native communities have been affected: Potsoteni, Saniveni, Boca Anapati, Samaniato, Caperucia, Pitziquia, Tziquireni, Centro Meteni, Fé y Alegría, Selva de Oro, and Sol Naciente.

Rojas said that the first report of a forest fire in the community of Potsoteni on August 19. Rojas’ statement aligns with observation made by a team from Mongabay Latam two weeks ago when they visited Potsoteni, located three hours from Puerto Ocopa along the Ene River. The fire appeared to have approached dangerously close to the community; even a few meters from its boundaries the reporting team found traces of a massive fire that occurred days earlier.

The fire reached several hectares of land and affected yucca crops, the primary source of food for the population, according to Walter Tishirovanti, community chief of Potsoteni.

“The fire is near the Otishi Park. They have ruined crops. I do not know what is going to supply the people of the community,” Tishirovanti told Mongabay Latam.

Local residents have been affected by the fires, and some have lost their staple crops. Photo courtesy of the Río Tambo District Municipality

CARE’s Rojas said defense against the fires has been solely the responsibility of community-members.

“So far the state has not done anything concrete” Rojas told Mongabay Latam.

A changing climate

All interviewees for this report agree that sudden changes in the regional climate have played a hand in the fires. Mayor Ivan Cisneros says that there is currently a severe drought in the district of Río Tambo: many waterholes have dried up and “the communities and the people are experiencing water shortages for human consumption.” The temperature has reached high levels, with peaks of 40 degrees Celsius, which is “highly unusual” and something that had not happened for at least 30 years, Cisneros told Mongabay Latam. He also mentioned that due to the effects of climate change they have “had the strongest summer in the history of the district, and because of that the forest is very susceptible to any fire. Even the green plants catch fire.”

This snake died in the blaze. Photo courtesy of the Río Tambo District Municipality

Marco Pastor of SERNANP warns that it is not the only place where fires have been reported: “this season we had fires in Ayacucho and one near Cusco. Right now there is one in Cusco. They are outside protected areas, but they are generating multiple foci due to the extremely dry weather conditions. We are now at the end of September and the rainy season should start. In some cases [fires occur] due to the people who suddenly burn the land and the fire turns out of control.”

As of press time, the fires continue to spread. Ernesto Ráez, one of the experts who signed the letter warning authorities, sees a clear way out to prevent these disasters: “we need to prohibit burning, it is simple. If we are experiencing dry conditions with high temperatures, people should not burn land because it will go out of control.” Ráez says that this ban should be treated differently in each region, “in the areas with risk of fires burning out of control, for example near woods or farms, the ban should be enforced, or in situations where there is a short forecast notice that indicates strong winds or high temperature.

Cisneros told Mongabay Latem that he feels powerless because he hasn’t found a solution to the problem. On Thursday, he approached the Congress of the Republic of Peru to seek help from lawmakers.

No comments:

Post a Comment