What is Global Warming?

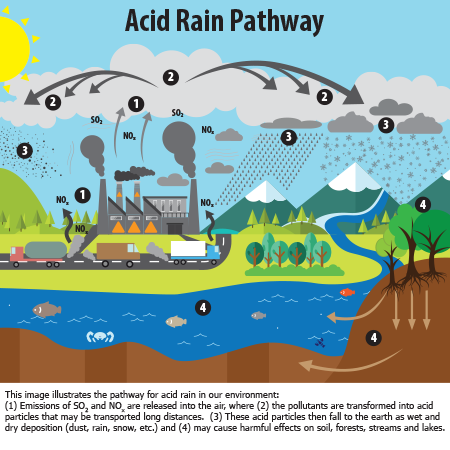

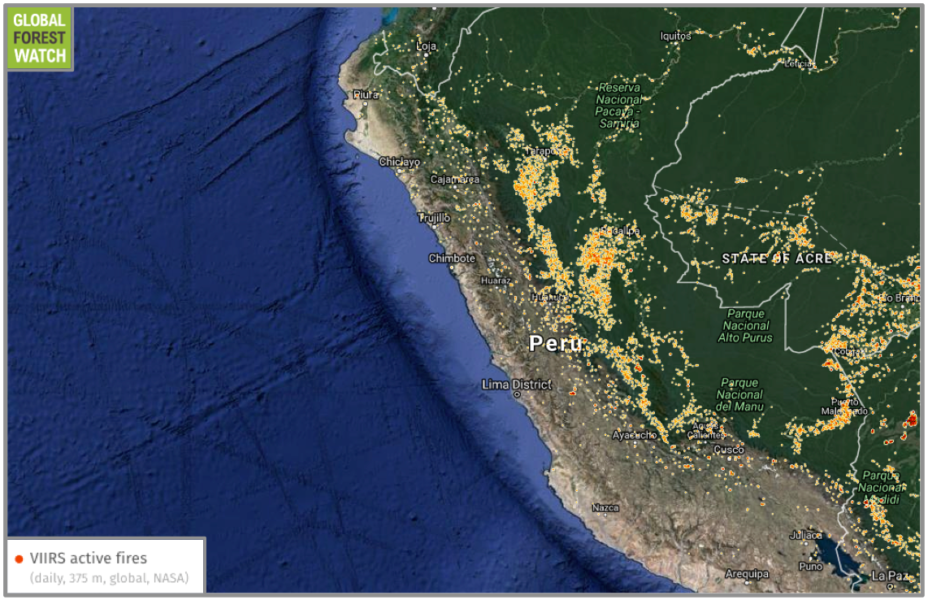

Global Warming is the increase of Earth's average surface temperature due to effect of greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels or from deforestation, which trap heat that would otherwise escape from Earth. This is a type of greenhouse effect.

Is global warming, caused by human activity, even remotely plausible?

Earth's climate is mostly influenced by the first 6 miles or so of the atmosphere which contains most of the matter making up the atmosphere. This is really a very thin layer if you think about it. In the book The End of Nature, author Bill McKibbin tells of walking three miles to from his cabin in the Adirondack's to buy food. Afterwards, he realized that on this short journey he had traveled a distance equal to that of the layer of the atmosphere where almost all the action of our climate is contained. In fact, if you were to view Earth from space, the principle part of the atmosphere would only be about as thick as the skin on an onion! Realizing this makes it more plausible to suppose that human beings can change the climate. A look at the amount of greenhouse gases we are spewing into the atmosphere (see below), makes it even more plausible.

What are the Greenhouse Gases?

The most significant greenhouse gas is actually water vapor, not something produced directly by humankind in significant amounts. However, even slight increases in atmospheric levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) can cause a substantial increase in temperature.

Why is this? There are two reasons: First, although the concentrations of these gases are not nearly as large as that of oxygen and nitrogen (the main constituents of the atmosphere), neither oxygen or nitrogen are greenhouse gases. This is because neither has more than two atoms per molecule (i.e. their molecular forms are O2 and N2, respectively), and so they lack the internal vibrational modes that molecules with more than two atoms have. Both water and CO2, for example, have these "internal vibrational modes", and these vibrational modes can absorb and reradiate infrared radiation, which causes the greenhouse effect.

Secondly, CO2 tends to remain in the atmosphere for a very long time (time scales in the hundreds of years). Water vapor, on the other hand, can easily condense or evaporate, depending on local conditions. Water vapor levels therefore tend to adjust quickly to the prevailing conditions, such that the energy flows from the Sun and re-radiation from the Earth achieve a balance. CO2 tends to remain fairly constant and therefore behave as a controlling factor, rather than a reacting factor. More CO2 means that the balance occurs at higher temperatures and water vapor levels.

How much have we increased the Atmosphere's CO2 Concentration?

Is the Temperature Really Changing?

Yes! As everyone has heard from the media, recent years have consistently been the warmest in hundreds and possibly thousands of years. But that might be a temporary fluctuation, right? To see that it probably isn't, the next graph shows the average temperature in the Northern Hemisphere as determined from many sources, carefully combined, such as tree rings, corals, human records, etc.

These graphs show a very discernable warming trend, starting in about 1900. It might seem a bit surprising that warming started as early as 1900. How is this possible? The reason is that the increase in carbon dioxide actually began in 1800, following the deforestation of much of Northeastern American and other forested parts of the world. The sharp upswing in emissions during the industrial revolution further added to this, leading to a significantly increased carbon dioxide level even by 1900.

Thus, we see that Global Warming is not something far off in the future - in fact it predates almost every living human being today.

How do we know if the temperature increase is caused by anthropogenic emissions?

Computer models strongly suggest that this is the case. The following graphs show that 1) If only natural fluctuations are included in the models (such as the slight increase in solar output that occurred in the first half of the 20th century), then the large warming in the 20th century is not reproduced. 2) If only anthropogenic carbon emissions are included, then the large warming is reproduced, but some of the variations, such as the cooling period in the 1950s, is not reproduced (this cooling trend was thought to be caused by sulfur dioxide emissions from dirty power plants). 3) When both natural and anthropogenic emissions of all types are included, then the temperature evolution of the 20th century is well reproduced.

Is there a connection between the recent drought and climate change?

Yes. A recent study by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration gives strong evidence that global warming was a major factor.

Who studies global warming, and who believes in it?

Most of the scientific community, represented especially by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC - www.ipcc.ch), now believes that the global warming effect is real, and many corporations, even including Ford Motor Company, also acknowledge its likelihood.

Who are the IPCC?

In 1998, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), in recognition of the threat that global warming presents to the world.

The IPCC is open to all members of the UNEP and WMO and consists of several thousand of the most authoritative scientists in the world on climate change. The role of the IPCC is to assess the scientific, technical and socio-economic information relevant for the understanding of the risk of human-induced climate change. It does not carry out new research nor does it monitor climate related data. It bases its assessment mainly on published and peer reviewed scientific technical literature.

The IPCC has completed two assessment reports, developed methodology guidelines for national greenhouse gas inventories, special reports and technical papers. Results of the first assessment (1990--1994): confirmed scientific basis for global warming but concluded that ``nothing to be said for certain yet''. The second assessment (1995), concluded that `` ...the balance suggests a discernable human influence on global climate'', and concluded that, as predicted by climate models, global temperature will likely rise by about 1-3.5 Celsius by the year 2100. The next report, in 2000, suggested, that the climate might warm by as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit over the next 100 years, which would bring us back to a climate not seen since the age of the dinosaurs. The most recent report, in 2001, concluded that "There is new and stronger evidence that most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to human activities".

Due to these assessments, debate has now shifted away from whether or not global warming is going to occur to, instead, how much, how soon, and with what impacts.

Global Warming Impacts

Many of the following "harbingers" and "fingerprints" are now well under way:

- Rising Seas--- inundation of fresh water marshlands (the everglades), low-lying cities, and islands with seawater.

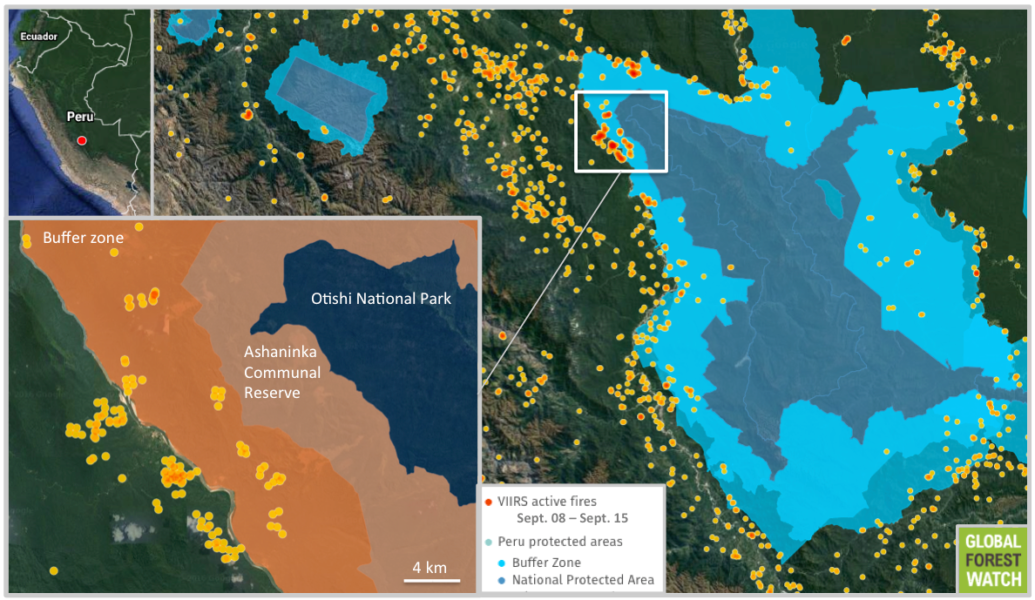

- Changes in rainfall patterns --- droughts and fires in some areas, flooding in other areas. See the section above on the recent droughts, for example!

- Increased likelihood of extreme events--- such as flooding, hurricanes, etc.

- Melting of the ice caps --- loss of habitat near the poles. Polar bears are now thought to be greatly endangered by the shortening of their feeding season due to dwindling ice packs.

- Melting glaciers - significant melting of old glaciers is already observed.

- Widespread vanishing of animal populations --- following widespread habitat loss.

- Spread of disease --- migration of diseases such as malaria to new, now warmer, regions.

- Bleaching of Coral Reefs due to warming seas and acidification due to carbonic acid formation --- One third of coral reefs now appear to have been severely damaged by warming seas.

- Loss of Plankton due to warming seas --- The enormous (900 mile long) Aleution island ecosystems of orcas (killer whales), sea lions, sea otters, sea urchins, kelp beds, and fish populations, appears to have collapsed due to loss of plankton, leading to loss of sea lions, leading orcas to eat too many sea otters, leading to urchin explosions, leading to loss of kelp beds and their associated fish populations.

Where do we need to reduce emissions?

In reality, we will need to work on all fronts - 10% here, 5% here, etc, and work to phase in new technologies, such as hydrogen technology, as quickly as possible. To satisfy the Kyoto protocol, developed countries would be required to cut back their emissions by a total of 5.2 % between 2008 and 2012 from 1990 levels. Specifically, the US would have to reduce its presently projected 2010 annual emissions by 400 million tons of CO2 . One should keep in mind though, that even Kyoto would only go a little ways towards solving the problem. In reality, much more needs to be done.

The most promising sector for near term reductions is widely thought to be coal-fired electricity. Wind power, for example, can make substantial cuts in these emissions in the near term, as can energy efficiency, and also the increased use of high efficiency natural gas generation.

The potential impact of efficiency should not be underestimated: A 1991 report to Congress by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Policy Implications of Greenhouse Warming, found that the U.S. could reduce current emissions by 50 percent at zero cost to the economy as a result of full use of cost-effective efficiency improvements.

Discussing Global Climate Change:

Here is a useful list of facts and ideas:

- Given the strong scientific consensus, the onus should now be on the producers of CO2 emissions to show that there is not a problem, if they still even attempt to make that claim. Its time to acknowledge that we are, at very least, conducting a very dangerous experiment with Earth's climate.

- A direct look at the data itself is very convincing and hard to argue with. Ask a skeptical person to look at the data above. The implications are obvious. The best source of data is probably the IPCC reports themselves, which are available at www.ipcc.ch (see, for example, the summaries for policy makers).

- The recent, record-breaking warm years are unprecedented and statistically significant. It is a fact that they are very statistically unlikely to be a fluctuation (and now we can point to specific side effects from those warm temperatures that appear to have induced recent worldwide drought).

- Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, whether or not you believe in global warming per se, the fact remains that the carbon dioxide levels are rising dramatically --- there is no debate about this. If we continue to use fossil fuels in the way we presently do, then the amount of carbon we will release will soon exceed the amount of carbon in the living biosphere. This is bound to have very serious, very negative effects, some of which, such as lowering the pH of the ocean such that coral cannot grow, are already well known.

Response of Government: Develop "Carbon Sequestration" Technology

Many government agencies around the world are very interested in maintaining fossil fuel use, especially coal. It should be noted that US energy use, which is enormous, is increasing, not decreasing. Furthermore, we are not going to run out of coal in the near term (oil may begin to run low sometime after 2010). Methods for reducing carbon emission levels while still burning coal are now investigation by government and industry, as we now discuss.

We believe that a major increase in renewable energy use should be achieved to help offset global warming. While there are some US government programs aimed in this direction, there is simply not enough money being spent yet to achieve this goal in a timely manner. A primary goal of many new programs is not to increase renewables, but rather, is to find ways to capture the extra CO2 from electricity generation plants and "sequester" it in the ground, the ocean, or by having plants and soil organisms absorb more of it from the air.

Possible Problems with Carbon "Sequestration"

One of the Carbon sequestration approaches under investigation is the possibility of depositing CO2 extracted from emission streams in large pools on the Ocean bottom. It is possible that such pools will not be stable, and may either erupt to the surface, or diffuse into the ocean and alter the oceans pH.

Another scheme under investigation is the idea of stimulating phytoplankton growth on the ocean surface by dusting the surface with iron (the limiting nutrient). This will cause an increased uptake of carbon by the plankton, part of which will find its way to the ocean bottom. Fishing companies are considering using this to increase fish harvests while simultaneously getting credit for carbon sequestration. Serious ecological disruptions could occur, however, especially if this approach is conducted on a sufficiently large scale.

Another idea is to stimulate Earth's terrestrial ecosystems to take up more carbon dioxide. While the impacts here are more difficult to ascertain, an important point to note is that these systems are not thought to be able to completely absorb all the extra CO2 . At best, they may be sufficient to help the US stabilize carbon emission rates for a few decades, but even if this is achieved, stabilization of rates are not likely to return the Earth to pre-industrial carbon levels. Worse, biological feedbacks to global warming, such as forest fires, drying soils, rotting permafrost, etc, may actually greatly accelerate carbon emissions, i.e. we may experience massive carbon de-sequestration.

Another major approach under consideration is to pump CO2 into old oil and gas wells. While seemingly attractive, it must be kept in mind that for this to be truly effective, it would have to be done on a world wide scale, include many sources of CO2 , including many sources which are presently small and widely distributed (such as car emissions, and not just coal plant emissions). All of this CO2 would need to be captured, transported, injected into old wells, and then the wells would need to be sealed and monitored. It is not clear that this would be affordable at all, and that there would be adequate capacity or assurance that CO2 would not leak out in massive quantities.

In the worst case scenario, carbon sequestration efforts may simply fail, but also end up being a political tool that is used to seriously delay a transition to renewable energy sources, and also possibly create many new environmental problems problems while prolonging old ones.

In the best case scenario, given the truly enormous amount of CO2 we are presently emitting, some sequestration approaches may serve as a useful bridge to curbing emissions while the transition to renewables is being made.